Traffic on the Stage

Play Texts and Stage Directions

Early modern play texts are complex documents, often difficult to decipher and modern editors go to great lengths to create editions that help the reader understand the action of the plays. In doing so, they often add exits and entrances that are missing from the original text. Without these added stage directions the plays are can be confusing to the reader and to the potential producer of the plays. The best modern editors approach the plays with an awareness of early modern theatre and printing practices and develop editions that indicate their own departures from the first printed editions of the plays: added stage directions will appear in square brackets – like this [Exit], or Enter Hamlet [reading a book] where the original text indicates Hamlet’s entrance but the fact that he is reading a book is the editor’s own interpretation of evidence found elsewhere in the scene. Many editions, however, do not mark the editor’s deviations from the original and without careful attention to footnotes it is not easy to deduce which stage directions were present in the original text and which were added.

The SQM company worked with new modern spelling editions of the plays in which additional stage directions were marked in square brackets. In rehearsal, however, these additional directions were treated as speculative and conditional and all options were considered before the staging of the scenes was finalized. The first printed editions of the three plays all lack important information about the traffic on and off the stage and contain several particularly complex scenes which demanded detailed analysis and experimentation before staging solutions could be found. Our objective was always to develop staging that satisfied the majority of stage directions in the texts. While the authority of those editions is itself dubious, subject as they were to the vagaries of early modern printing practice, they remain the main documentary evidence on the staging practice of the Queen’s Men.

The Queen’s Men were a touring company and had to be able to present their performances in a variety of venues. The SQM project was designed to examine the particular challenges created when a company had to prepare plays for multiple venues and different staging arrangements. Working with two different stage configurations and in numerous venues, the actors had to develop blocking protocols that were adaptable to the different spaces. The SQM case studies are designed to take you through the decision-making process that determined the SQM staging of particularly challenging sections of text from the three plays.

The SQM Stages

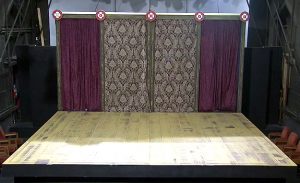

The Tavern Stage

Our three plays demand, at minimum, a bare stage with two exits/entrances and that the actors can access both exits/entrances from back stage. We referred to this configuration as the “tavern stage” as we imagine this is the kind of thing that might easily have been set up in the inn-yards or interior rooms of the taverns that the Queen’s Men visited on tour. It is comparable to stages in the theatres that were later built in London.

The Swan Theatre

This is sketch of the interior of the Swan theatre drawn by an eyewitness, a Dutch tourist named Johannes de Witt. It is the only contemporary image we have of the interior of an Elizabethan professional theatre. Strip away the trimmings and both stages are quite simple featuring a rectangular playing area which can be accessed through two entrances at the back. The curtains on our stage are equivalent to the two doors on the drawing of the Swan.

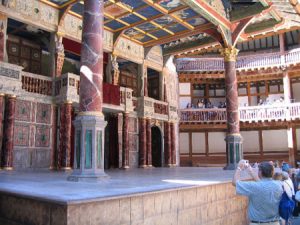

Shakespeare’s Globe

This is an image of the newly built Shakespeare’s Globe theatre in London, England. Here you will see there is another opening in the centre of the back wall. This is what is often referred to as a discovery space. It is thought that it might have been used to represent interior rooms like Friar Bacon’s study or Juliet’s bedroom or to reveal surprises such as the statue of Hermione at the end of Winter’s Tale.

Smaller But Similar

Although on a much smaller scale, the central panel of curtains on our stage could also be used as a discovery space. The curtained space at the back is referred to as the tiring house and is where the actors changed their costumes. Since the Queen’s Men were a touring company and would of necessity have worked on a variety of stages, our stage was designed so that it could be re-configured to create a different relationship between the actors and the audience.

The University Stage

This stage was based on Alan Nelson’s research on the demountable stage used at Trinity College, Cambridge. Nelson established that the important members of the audience sat behind the stage and that there were two tiring houses on either side of the stage. While there is no evidence that this arrangement was common in Elizabethan England it was so striking an arrangement that we felt it worthy of experiment. To our knowledge, Elizabethan plays have not been performed in such a setting since. It proved to be an awkward space to work in for the actors, as the important members of the audience were sitting behind them. But sitting on the stage did actually feel like a privileged position even though one was often confronted by the actors’ backs. Audience members sitting on the stage reported that they felt involved in the action as though they were living in the scene with the actors. The actors also learned to play to the hierarchy created by the on-stage audience, referring lines about the court to that section of the audience and addressing references to commoners or appeals to the people out front. See the opening scene of Friar Bacon as performed on this stage.

Other Settings

On our brief tour of Hamilton and Toronto, we also performed the play with no stage at all. This is a performance in Quarters, the student union bar at McMaster University. For this performance we strung the curtains along the back of the space and gathered chairs and tables around to form a semi-circle playing space in front of them. The actors freely improvised in this space, interacting with the audience and taking some of the action out into and behind the audience.

The Court Setting

This was the stage for our final performance of King Leir at University College, University of Toronto. The room is configured to represent a performance at court. The queen sits at one end of the hall on full display flanked by important dignitaries. Other important nobles sit on a scaffold opposite. The photograph is taken from the nobles’ scaffold. The action of the play takes place in the space between them with lesser nobles seated on either side.

Preparing Plays for Touring

problems presented by performing in different spaces and different configurations night after night was an additional challenge for our modern actors, who were already expected to prepare three plays for performance in the time it would usually take them to prepare two.

Blocking Different Venues

As the company director/facilitator, I was concerned about the amount of new information and new techniques I was asking the actors to learn in a short space of time. I needed to find a way to make the actors comfortable when approaching the constantly changing conditions of performance. I initially created a blocking plot for each play, marking characters’ entrances and exits on in little diagrams on my script. The technique was laborious and complex and it became clear that however well I managed the traffic on the stage for the first productions, problems would arise when we started to move the show from venue to venue. I started to wonder how Elizabethan companies would have solved this problem.

Research

by Tiffany Stern

Tiffany Stern’s analysis of evidence on early modern rehearsal practice suggests the actors prepared for performance alone, studying their parts to learn their lines and cues. Once the lines were learnt the evidence implies that the full company would meet only once and rehearse for a maximum of four hours before performing the play in front of a live audience .

Prompt Books & Staging

The theatre companies kept track of movement on and off the stage in a prompt book. Several of these prompt books have survived but none of them indicate which door the characters should enter through except when two characters or groups of characters are entering the stage simultaneously through different doors.

Given the time constraints and the fact that specific doors were not recorded for entrances and exits, I felt that early modern theatre professionals must have had some shorthand or protocol actors could follow for every play. I decided to experiment with the possibility that characters always entered through one door and exited through another. I chose stage left for entrances and stage right for exits. The advantage of this simple system is that it avoids the possibility of collision and traffic problems as the characters get on and off the stage, since they will never try to enter and exit through the same door/curtain. This basic protocol proved to be very effective in practice and is one of the premises for the following exploration of the staging of the central King/Prince scenes in Famous Victories.

King Lear: The Sudden Banquet

Introduction

This staging puzzle comes from Scene 24 of King Leir. Cordella, her husband the King of France and his friend Mumford are taking a walk in the country disguised as commoners when they encounter King Leir and his friend Perillus, who are close to death from starvation. Read the text and ask yourself how it might be staged. Take note of all the references to food, drink and the specific mention of a table. When you have finished analyzing the text, go to the next page

Questions

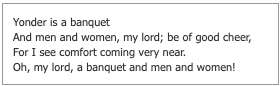

The scene implies that Leir and Perrilus sit at a table and eat but where does the food come from? There is also a specific reference in the stage directions to a table. How does the table get on stage? Or was it on stage all the time? The meal is referred to as a banquet. Does this indicate that there is a large table with a lot of food? Or is it simply that to the starving Perillus the small amount of food on offer seems like a banquet? How would you stage this scene and satisfy the majority of the stage directions? Is there actually a table on stage? Where does the food come from?

Staging the Scene

There were easier and more economical ways to stage this scene. Mumford could have laid a cloth on the stage and served out food from his basket. This could have seemed like a banquet to the starving Leir and Perillus. But this would have ignored the two clear references in the stage directions to a table. Another solution would be to have Mumford enter carrying a basket and a small trestle table at the start of the scene. He could then set up the table and lay out the food on cue. But this would not satisfy the implications of Perillus’ following lines:

There are two key factors here. First, Perillus refers to men and women in the plural; the stage directions so far have only marked entrances for the Gallia, Mumford and Cordella – two men but only one woman. Second, he says he sees “comfort coming very near” and the next line specifies that the “comfort” is “a banquet” which he then connects to the “men and women” he just mentioned. This was the evidence in the text on which we based our staging. Although there is no mention of the country folk in the stage directions, Cordella was talking about them earlier in the scene, having them come on stage carrying a table and food for a “banquet” made sense of Perillus’ confusing lines. But why were they singing?

King Leir: The Sudden Song?

There is no textual justification for the song but we discovered early in the process that our company were excellent singers and looked for any opportunity to exploit their talents. Furthermore, bringing a table and food onto the stage is a clumsy business, not interesting enough to stand alone, but too distracting to be executed behind dialogue. Covering this action with a song therefore made theatrical sense. Most of all, however, the song increased the focus on the symbolic importance of the action. Having been thrown out of the homes of his other two daughters, Leir here receives hospitality from apparent strangers. By adding the song and turning the arrival of the “banquet” into a small spectacle we were following the implications of the stage directions but also highlighting a central theme in the play.

Friar Bacon: Magic Spectacle

The battle of magic between the English friars Bacon and Bungay and the German scholar Vandermast explicitly demands spectacular stage effects. Read the text of this section of action and then watch the video below to see the SQM staging.

Another Staging Puzzle

Bacon’s other magic is much simpler and can be enacted simply through the actor’s performance. The sequence of action when the prince first meets the Friar presented the company with another series of puzzles. See if you can identify the tricky moments and through analyzing the text find ways it might creatively be staged.