Modern Acting

How does an actor decide how to say his or her lines? Every actor has their own way of developing a performance, but there is a shared language that most theatre actors understand which is derived from the work of Stanislavski and taught in most Western actor training programs. It is commonly referred to as the Method but there are in practice many methods in fact as many methods as there are actors. This module will introduce you to one such method by taking you through a step-by-step process through which an actor can turn text into a performance.

A Love Triangle: A Case Study

Introduction

Before an actor can analyze a scene, he or she must establish the background information that informs their characters’ actions in that scene. This background information is referred to as the “given circumstances.” Establishing the given circumstances of a scene involves a detailed knowledge of the play as a whole. To speed our process the answers to the central questions for this scene might be presented as follows:

Who are the characters?

- Edward is the Prince of Wales, heir to the throne of England.

- Lacy is an English aristocrat.

- Margaret is a commoner, the surprisingly beautiful and erudite daughter of a gamekeeper.

What relationship do they have to each other?

kidnapped by one of Bacon’s devils.

- Lacy and Edward are close friends.

- Edward is a Prince and therefore has authority over Lacy who is only an Earl.

- Lacy and Edward are in love with Margaret.

- Margaret is a commoner and therefore of inferior status to both characters.

- Margaret is in love with Lacy.

What has happened to these characters before the scene begins?

- Edward met Margaret by chance when hunting in the country and fell for her. He makes it clear in the first scene that his interests are sexual rather than romantic or honorable, complaining that “our country Margaret is so coy,/And stands so much upon her honest points,/That marriage or nor market with the maid.”

- Edward sends Lacy to woo Margaret on his behalf.

- Lacy does so and falls for Margaret himself.

- He proposes marriage and they are about to be married by Friar Bungay when a devil appears and carries the Friar away.

- Edward was watching them through Friar Bacon’s magic looking glass and asked Bacon to send the devil, which he did. Friar Bungay was carried to Oxford where he had dinner with Bacon and the Prince.

This information can all be gleaned from reading the play up to this point. There is much more information about the characters that could be used but this is the bare bones necessary to tackle this scene….

Understanding Objectives

Aristotle said that drama was an “imitation of an action.” This principle holds true for Western naturalistic acting technique. The creative process of the actor is designed to develop the dramatic action of a play. By this we mean far more than the actor’s physical activity on the stage. Although Method actors have a reputation for being overly emotional, uncovering the action is the central goal of their process. The principle question for the modern actor is: what is my character doing and why?

It is a basic principle of Western naturalistic acting that characters act with purpose, that the needs, desires, and intentions of characters drive the action of a play. They constitute the causal force that links one moment of a play to the next. Actors often use the term objective to describe the force that motivates their characters’ actions. An objective is a goal or desire, something that the character wants, or is trying to achieve.

Edward’s Objective

Each actor will look at the play principally from the perspective of their own character. For the purposes of this example, we will be focusing on Prince Edward (played by Paul Hopkins). We know the given circumstances of our scene from Friar Bacon.

Understanding Obstacles

Margaret has been the object of the Prince’s desires from the opening scene of the play. She is the objective that has motivated his actions. He sent Lacy to woo her on his behalf. He visited Bacon to ask for magical assistance in his seduction. Although the prince also wants vengeance on Lacy in this scene, Margaret is still his primary objective. From this perspective, Lacy is an obstacle to the Prince’s desires.

Obstacles are crucially important to acting since without resistance to a character’s will there is no conflict. Characters in drama struggle to overcome their obstacles in pursuit of their objectives. While characters usually have one clear objective, they often have many obstacles in their way.

Edward’s Obstacles

The text tells us that the prince enters with his “poinard in his hand” and it seems that the Prince intends to kill Lacy and thus remove the major obstacle to his objective. Lacy and Margaret are defenceless, so in principle he could simply kill Lacy and carry Margaret away, but he doesn’t do that. Why not? This may seem like a silly question but it is an important one. The actor has to decide what is stopping him from simply acting on his desire. What further obstacles are in his way?

In this instance we can rely on common sense and information from the given circumstances of the scene. The two most important obstacles to Edward here are the fact that:

1. Killing without a trial is illegal and dangerous even for a Prince especially when the victim is a powerful Earl.

2. Lacy was Edward’s close friend.

Understanding Actions

The final element in the process is to establish the characters’ actions: the things they do in their struggle to overcome their obstacles and achieve their objective? Remember: The notion of the character’s action includes much more than their movement upon the stage. We need to understand what Edward is doing with his words.

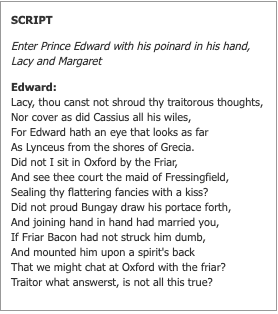

Edward’s Lines

Let’s look at Edward’s first sentence. Edward compares Lacy to Cassius, who betrayed Julius Caesar, and himself to Lynceus the grandson of Perseus who had preternaturally keen eyesight. His point is that the Lacy cannot hide his guilt. This is what the line means, but what is Edward doing?

Using Verbs to Define Action

One common technique used by actors to make their words as active as possible is to select appropriate verbs that describe what their characters are doing. An actor might decide his character his “seducing,” “scaring” or “persuading” the other character with his words.

The selection of an appropriate verb helps define the specific action that the character is taking in pursuit of its objective. There are actors and acting teachers that insist that each sentence the character speaks should be given an appropriate verb. Let’s look at the next section of text…

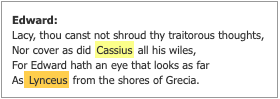

To Accuse or Challenge?

The first two highlighted questions describe the crimes that Lacy has committed. We might say that Edward is performing the action “to accuse” in this sentence. This is a good active word that encourages the actor to make the words work directly on his acting partner. Edward is accusing Lacy. This will help set up a causal pattern of action and reaction, but what about the next sentence? Do we need a different verb here?

We might say he is presenting evidence, but he was also doing that in his last sentence. Is there any valuable distinction to be made here based on the text alone? I would argue that there is no unequivocal textual evidence for a new action here. The benefit of choosing an action for each sentence is that the selection of relevant verbs can be used to give a specific active quality to the character’s words which adds texture and variety to the performance. In this instance, an actor might feel that it is not necessary to distinguish between these two questions but that he should back the last sentence with the verb to challenge. These are the kind of interpretive choices that are made by modern actors in the rehearsal process sometimes independently and sometimes working closely with the director.

Summary of the Action So Far

Edward wants Margaret to be his lover. Lacy has won her heart and has thus become an obstacle to the Prince’s objective. Killing Lacy is an obvious means to remove this obstacle. The prince enters with his dagger drawn intimidates Lacy and then accuses him of treachery, challenging him to deny the crime. How does this action serve his objective?

If Lacy is a traitor, then the Prince would be justified in killing him – treachery is a capital crime. It would not hold up in a court of law but the important thing is that it would seem justified to the prince. Edward is attempting to remove one of the obstacles preventing him from killing Lacy, or to describe the action from Edward’s perspective, he is executing justice on a traitorous subject who has stolen the affections of love.

Lacy’s Response

For the next section we have to shift the perspective to the character of Lacy. Lacy is being threatened with a dagger by his old friend, a powerful prince, whom he has betrayed. He is in a situation of extreme jeopardy and his initial objective must be to save his own life. His principal obstacle is his old friend the prince and the fact he is being rightly accused of treachery. Now, let’s take a look in the script at what Lacy says…

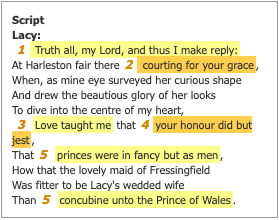

1. Truth all

Lacy first admits his guilt. Is the prince surprised? Perhaps surprised enough to listen to Lacy’s “reply?”

2. Good Intentions

Lacy establishes that he went with good intentions to woo Margaret on Edwards’ behalf.

3. Lacy Blames the Power of Love

Lacy says he then became subject to the power of Love, which removes some of the blame for his actions.

4. Lacy Questions the Prince’s Motives

The Prince’s affection for Margaret was not sincere, but rather, a “jest” or game.

5. Lacy Appeals to his Prince’s Honour and Sense of Morality

Princes are just men and thus subject to the power of “fancy” or love. Just because they are royalty does not mean they always act honorably. Marrying the lovely maid of Fressingfield was the right thing to do when the alternative was to allow her to become a royal “concubine” or prostitute.

Lacy’s speech is very clever. His action is to defend himself and justify his disobedience. By the end of the speech he has turned the table on the prince and accused him of dishonorable intentions. Although he is subject to the power of the prince he is still a powerful aristocrat and the king’s power was absolute only in theory. Kings that behaved tyrannically as the prince is here risked provoking rebellion amongst their subjects. Lacy is fighting back. But what has the prince heard? The only way to deduce this is to look at what he says in

Edward’s Response

What will the Prince say in response to Lacy?

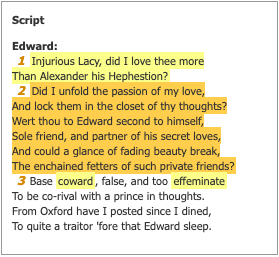

1. Did I love thee more…?

Through his rhetorical question, the Prince compares his love for Lacy with the classic example of platonic love between two male soldiers. (The fact that Alexander and Hephestion were lovers was not commonly known at the time.)

2. Private Friends

The next two questions are reminiscent of Edward’s first speech but the topic here is Lacy’s betrayal of trust and more specifically the fact that, subject to the love of a woman, he has betrayed the trust between two men.

3. Honour Amongst Men

He calls Lacy “coward” and “effeminate” because the Earl has allowed feminine love to break his bonds of honour with a man.

Interestingly, the prince does not directly address the arguments presented by Lacy; he does not defend himself from Lacy’s accusation that he was going to make Margaret his concubine. Instead, he recalls their friendship as an ideal of masculine love and attacks Lacy’s manhood and honour. The Prince is picking up on Lacy’s challenge to his honour, but the shift of focus implies that while he was listening to Lacy, the questions about his motives were secondary to the fact that his old friend had betrayed him – his first two words “Injurious Lacy” are persuasive evidence that Lacy’s betrayal is in the forefront of his mind.

The process I am taking you through is one of analysis and discovery and at every turn there are various possible answers to the questions presented. The goal is to find the actions that allow the actors to play out the scene and justify all the things their characters say and do, creating a causal chain of action and reaction. There are no absolutes here: each actor finds their own way through a script and part of the pleasure in theatre is that no two performances will be the same.

On the page Edward’s words look very similar to his first speech and we might select similar verbs to help make the language active. As a director, I might tell the actor to use these words to boldly challenge Lacy’s honour and attack his manhood, but let’s watch how Paul Hopkins chose to interpret this moment in performance.

Did You Notice?

As he listens to Lacy, Edward sees his old friend plead eloquently in his defense and, while he is offended and returns accusation for accusation, his speech at first has a reflective and sorrowful quality as he recalls their lost friendship. It is as if he is adding adverbs to his action – he is accusing sorrowfully, or mournfully. At “Base coward..” he resumes a more aggressive tone, driving through to the articulation of his intention to take vengeance on the “traitor” Lacy. This is not the only way it might be performed but it is an effective choice and one that our Lacy picked up on in performance.

Paul’s choice was a strong one. It was based on firm evidence in the text and helped set up a later moment in the scene by making Lacy confront the fact he has betrayed his friend. It is important that the prince’s arguments hit home with Lacy as later in the scene Lacy accepts his guilt and says he deserves to be killed. First however, Margaret intervenes.

Margaret’s Intervention

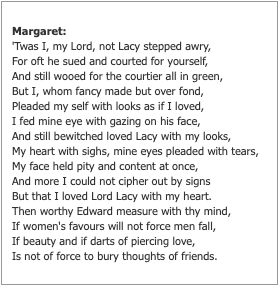

Margaret insists the blame is her own, saying it is not unusual that women should persuade men to forget their friends.

But what does Edward hear?

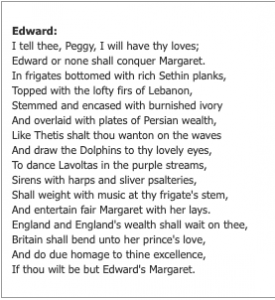

Not a lot, it would seem. He starts his sentence as though he is answering Margaret but what he says bears no relation to what she just said. He has been struck once more by Cupid’s dart, seeing Margaret as if for the first time in the scene and loving her all over again, a kind of love at second sight. Lacy is forgotten for the moment and this supports my argument that vengeance on Lacy is not Edward’s primary objective in the scene. Hearing Margaret speak has reminded him what he really wants from this scene, and he now sets about getting it by seducing her with fanciful imagery and the promise of riches.

A Complex Spectacle of Love

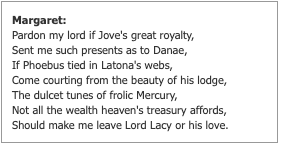

Margaret’s Response

In response to his efforts Margaret uses several classical references to make it clear to the prince that she is not to be seduced and nothing will tempt her to leave Lacy. This time the Prince hears her as he decides on a new course of action returning his attention to Lacy.

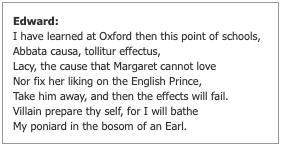

The Prince Responds

Through the application of university learning, the prince decides he can win Margaret’s love by removing the present object of her affections – genius! The struggle resumes. Edward does not kill Lacy in the end and bearing in mind our analysis to this point watch the scene play out and consider why Edward spares his old friend.

Queen’s Men Acting Style

But how did the Queen’s Men do it?

The rehearsal techniques discussed in this module derive from approaches to acting common today. Not all actors work in this way but most know the language and have adapted it for their own uses. As you will have noticed, the process is time consuming. The increasing dominance of Stanislawski’s rehearsal techniques coincided with an increase in the amount of time given to rehearsal in Western theatre. The actors in early modern London did not dedicate nearly as much time to rehearsal. In fact, evidence suggests that actors would prepare their roles on their own congregating as an ensemble only for four hours before the first performance of a play. The London companies performed a different play on every day of the week barring Sunday and brought a new play to the stage as often as every second week. They could not have possibly dedicated as much time as modern actors do to the preparation of their roles.

Early modern actors did not rehearse together as modern actors do today; they “studied” their “parts” alone.1 The principal goal of such study was memorization but actors would also work on establishing the correct emphasis for the words and finding the physical actions that best suited those words. As Hamlet most famously puts it in his advice to the players: “Suit the action to the word, the word to the action” (3.2.16-17). The principles of oratory taught in English grammar schools provided clear guidelines on the correct pronunciation and emphasis for different rhetorical tropes and the appropriate actions that should be used to support the words. It is likely that the early modern actors when they had grammar school educations drew on this knowledge when studying their parts. Master actors likely trained their apprentices in the arts of rhetoric and oratory. Given the speed with which new plays were prepared for the stage, there could have been little time for the kind of psychological analysis that is the focus of the modern actor’s process.

The SQM rehearsal schedule increased the time pressure on the actors and Paul Hopkins found that it was impossible to follow his usual preparation process. The actors discovered that the discursive and exploratory rehearsal practices that we use to deepen our understanding of character and text had to take second place to the simple but urgent imperative of memorization.

Does this mean that, in comparison to modern performances, the early modern actors’ performances were superficial? Were their performances repetitious renditions of correct pronunciations performed with overly familiar gestures and action? The popularity of the theatre in England at this time suggests not. Eyewitness accounts of actors’ performances usually praise them for their life-like quality and for their emotive power.2 So how did the early modern actors create compelling, life-like performances while working alone and within relatively rigid rules of oratory? And how might their process relate to the modern actor’s process?

There is in fact a strong connection between modern actor’s process and our understanding of an early modern player’s process focused on rules of rhetoric and oratory. Rhetoric is the art of persuasive writing; oratory the art of persuasive speaking. Rhetorical language is designed to affect the listener, to move them to change their opinions or their course of action. Rhetorical language is thus active language and has great affinity with the modern actor’s techniques, explored above, which are focused on turning text into dramatic action. The modern actors’ exploration of given circumstances, objectives and obstacles reveals what the characters are doing to each other with their words. The difference is that Stanislawski was largely working with naturalistic text where the dramatic action is sub-textual, operating beneath the surface of the dialogue, whereas the early modern players were working with poetry whose figures and conceits were specifically designed to actively affect the listener.

Peter Higginson felt that the very structure of the SQM process necessitated an increased application to and reliance on the text. The details of the character and clues to his performance could all be found in his part. In theory, applying yourself to the rhetoric of the text can activate a performance as much as a detailed study of the given circumstances, objectives, obstacles and actions. John Barton in his famous video series Playing Shakespeare makes this connection between rhetoric and Stanislawski’s theory of the objective, and most Western classical actor training is now text-centered and focuses on releasing and channeling the active power of the words.

Such a rhetorical approach works well when working with Shakespeare and plays written by similarly skilful rhetoricians and dramatists but the Queen’s Men plays are not always so skillfully written. The verse of King Leir proved to be the best of the three. In comparison to Shakespeare, there is a scarcity of concrete images and multi-syllabic words which makes it very difficult to memorize but we found that following a regular iambic rhythm would lead the actor to stress the words that made most sense of the lines. The verse in Friar Bacon more closely resembles Shakespeare: it is full of complex images and classical references but working with this text proved problematic. The actors discovered that many of the clauses and sentences were incomplete. Often the sense and intention was apparent but not supported by the grammar. In these instances, actors had to establish their characters’ intentions and attempt to play those intentions rather than following the structure of the verse. Famous Victories was a challenge of an altogether different sort. The play is written in loose prose throughout and the rules of rhetoric would be little help deciphering the characters’ intentions. The actors were forced to look at the circumstances of the scenes and their characters’ backgrounds to bring the dramatic action to life.

The psychological techniques of the modern actor and the rhetorical technique of the early modern actor can result in comparable effects when working with high quality dramatic verse. But the early modern actors must have had other resources to draw on when working with texts such as Famous Victories.

Time Pressure and Character Development

Observing the SQM company working under the time pressure of our rehearsal process, I was able to watch the actors develop their facility to quickly turn text into action. As they became increasingly familiar with the material and the world of the original company they were able to transfer lessons learnt in the early plays onto the later plays. Distinctions between different classes became automatic and actors playing more than one character in the play made simple bold choices to distinguish between them. The master actors took more control in the rehearsal process, quickly establishing the feeling of a scene based on their interpretation of the circumstances. Paul Hopkins playing the prince in Friar Bacon called for a locker room atmosphere for the opening scene where he describes his encounter with Fair Margaret. Once this basic context was established each actor was able to develop his performance in line with that context. This interpretation was also a development of the relationship Paul had developed between his Prince Henry in Famous Victories and his side-kicks Ned, Tom and Jockey. The similarity between characters and relationships in the different plays accelerated the development of the action during the rehearsal of Famous Victories and Friar Bacon. Discovering connections between the plays allowed the company to develop a short-hand when preparing scenes, as repeating familiar patterns saved precious time allowing the actors to focus on memorization rather than discussing interpretation.

As they spent more time working together the company also developed the ability to find new interpretations on their feet. The rehearsals took on an improvisatory feel. Once the lines were in place and the actors had a basic grasp of their characters’ circumstances and intentions, they were able to respond spontaneously to each other, developing the dramatic action and new stage business as they played through their scenes. This playful quality carried over into the performances and was a major factor in their success. The performances sustained a live quality throughout and as they grew in confidence actors started to invent new business in front of the live audience. A modern approach to acting can also generate these qualities but I would argue that generally it is inclined towards fixing a theatrical performance by opening night and then repeating it. The very nature of the SQM rehearsal process encouraged an improvisatory approach to performance.

Given the fact that early modern actors spent even less time rehearsing together than our company, it seems likely that their approach to performance was similarly spontaneous. We know that their clowns were famous for improvising, but this improvisatory quality impacts the performances of all the characters. The very uncertainty of the lines increases the sense of contingency that gives performance its live quality. There are negative consequences to this uncertainty as actors’ nerves can get the better of them, lines can be lost and so on, but as our company grew in confidence we started to see the advantage of such a system. The performances became living, breathing organisms that developed in new ways each night through the dynamic interactions of the actors with each other and with the audience. All theatre is like that to some extent, but the SQM process seemed especially attuned to creating such theatre.